Holocaust denial is not protected by the European Convention on Human Rights

Ιn the case

of Pastörs v. Germany (application no. 55225/14) the European Court of Human

Rights held on 3.10.2019, unanimously, that the applicant’s complaint under Article 10

(freedom of expression) was manifestly ill-founded and had to be rejected, and,

by four votes to three that there had been no violation of Article 6 § 1 (right

to a fair trial) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The case

concerned the conviction of a Land deputy for denying the Holocaust during a

speech in the regional Parliament. The Court found in particular that the

applicant had intentionally stated untruths to defame Jews. Such statements

could not attract the protection for freedom of speech offered by the

Convention as they ran counter to the values of the Convention itself. There

was thus no appearance of a violation of the applicant’s rights and the

complaint was inadmissible.

The Court

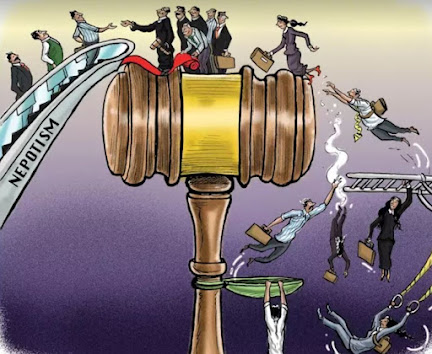

also examined a complaint by the applicant of judicial bias as one of the Court

of Appeal judges who had dealt with his case was the husband of the

first-instance judge. It found no violation of his right to a fair trial

because an independent Court of Appeal panel with no links to either judge had

ultimately decided on the bias claim and had rejected it.

Principal

facts

The

applicant, Udo Pastörs, is a German national who was born in 1952 and lives in

Lübtheen (Germany). On 28 January 2010, the day after Holocaust Remembrance

Day, Mr Pastörs, then a member of the Land Parliament of Mecklenburg-Western

Pomerania, made a speech stating that “the so-called Holocaust is being used

for political and commercial purposes”. He also referred to a “barrage of

criticism and propagandistic lies” and “Auschwitz projections”.

In August

2012 he was convicted by a district court, formed of Judge Y and two lay

judges, of violating the memory of the dead and of the intentional defamation

of the Jewish people. In March 2013 the regional court dismissed his appeal

against the conviction as ill-founded. After reviewing the speech in full, the

court found that Mr Pastörs had used terms which amounted to denying the

systematic, racially motivated, mass extermination of the Jews carried out at

Auschwitz during the Third Reich.

The court

stated he could not rely on his free speech rights in respect of Holocaust

denial. Furthermore, he was no longer entitled to inviolability from

prosecution as the Parliament had revoked it in February 2012 He appealed on

points of law to the Court of Appeal which, in August 2013, also rejected his

case as ill-founded. At that stage he challenged one of the judges adjudicating

his appeal, Judge X, claiming he could not be impartial as he was the husband

of Judge Y, who had convicted him at first instance.

A

three-member bench of the Court of Appeal, including Judge X, dismissed the

complaint, finding in particular that the fact that X and Y were married could

not in itself lead to a fear of bias. Mr Pastörs renewed his complaint of bias

against Judge X before the Court of Appeal, adding the other two judges on the

bench to his claim. In November 2013 a new three-judge Court of Appeal panel,

which had not been involved in any of the previous decisions, rejected his

complaint on the merits. Lastly, the Federal Constitutional Court declined his

constitutional complaint in June 2014.

Complaints,

procedure and composition of the Court

Relying on

Article 10 (freedom of expression) and Article 6 § 1 (right to a fair trial),

Mr Pastörs complained about his conviction for the statements he had made in

Parliament and alleged that the proceedings against him were unfair because one

of the judges on the Court of Appeal panel was married to the judge who had

convicted him at first instance and could therefore not be impartial. The

application was lodged with the European Court of Human Rights on 30 July 2014

Decision of

the Court

Article 10

(freedom of Expression)

As with

earlier cases involving Holocaust denial or statements relating to Nazi crimes,

the Court examined Mr Pastörs’ complaint under both Article 10 and Article 17

(prohibition of abuse of rights). It reiterated that Article 17 was only

applicable on an exceptional basis and was to be resorted to in cases

concerning freedom of speech if it was clear that the statements in question

had aimed to use that provision’s protection for ends that were clearly

contrary to the Convention.

The Court

noted that the domestic courts had performed a thorough examination of Mr

Pastörs’ utterances and it agreed with their assessment of the facts. It could

not accept, in particular, his assertion that the courts had wrongfully

selected a small part of his speech for review. In fact, they had looked at the

speech in full and had found much of it did not raise an issue under criminal

law.

However,

those other statements had not been able to conceal or whitewash his qualified

Holocaust denial, with the Regional Court stating that the impugned part had

been inserted into the speech like “poison into a glass of water, hoping that

it would not be detected immediately”.

The Court

placed emphasis on the fact that the applicant had planned his speech in

advance, deliberately choosing his words and resorting to obfuscation to get

his message across, which was a qualified Holocaust denial showing disdain to

its victims and running counter to established historical facts. It was in this

context that Article 17 came into play as the applicant had sought to use his

right to freedom of expression to promote ideas that were contrary to the text

and spirit of the Convention.

Furthermore,

while an interference with freedom of speech over statements made in a

Parliament deserved close scrutiny, such utterances deserved little if any

protection if their context was at odds with the democratic values of the

Convention system. Summing up, the Court held that Mr Pastörs had intentionally

stated untruths in order to defame the Jews and the persecution that they had

suffered. The interference with his rights also had to be examined in the

context of the special moral responsibility of States which had experienced

Nazi horrors to distance themselves from the mass atrocities. The response by

the courts, the conviction, had therefore been proportionate to the aim pursued

and had been “necessary in a democratic society”.

The Court

found there was no appearance of a violation of Article 10 and rejected the

complaint as manifestly ill-founded.

Article 6 §

1 (right to a fair trial)

The Court

reiterated its subjective and objective tests for a court or judge’s lack of

impartiality: the first focused on a judge’s personal convictions or behaviour

while the second looked at whether there were ascertainable facts which could

raise doubts about impartiality. Such facts could include links between a judge

and people involved in the proceedings. It held that the involvement in the

case of two judges who were married, even at levels of jurisdiction which were

not consecutive, might have raised doubts about Judge X lacking impartiality.

It was also

difficult to understand how the applicant’s complaint of bias could have been

deemed as inadmissible in the Court of Appeal’s first review, which had

included Judge X himself. However, the issue had been remedied by the review of

Mr Pastörs’ second bias complaint, which had been aimed at all the members of

the initial Court of Appeal panel and had been dealt with by three judges who

had not had any previous involvement in the case. Nor had the applicant made

any concrete arguments as to why a professional judge married to another

professional judge should be biased when deciding on the same case at a

different level of jurisdiction. There were thus no objectively justified

doubts about the Court of Appeal’s impartiality and there had been no violation

of Article 6. (

Read the Decision here

Comments

Post a Comment